He won't have any cake, he says, because he had a large lunch. Rosenthal doesn't believe in editing his stories - they come with myriad clauses and caveats and sidetracks and extraneous detail. Uhuh? We speak about art and the world and getting things together and dreams." Now Christos introduced me to the whole world of European art. We wanted to work together on a big project. For a long time we were a mutual appreciation society. So what was it all about? "David Sylvester was a good friend of mine. I'm actually a very meek and mild person." The spit spat, he says, was just a one-off. Ah, so you spit from a height when staff offend you, I say. I look over the balcony on to his office. Actually, we retire to the mezzanine above his office. At times, that passion has boiled over, most famously when he spat at the art writer and curator David Sylvester on the press night of a major exhibition. "I call it the Mona Lisa piece." There are 380 pieces here, more than 200 of them transported from Mexico. He tugs me towards his favourite Aztec sculpture - the Moon Goddess.

Technique is important, but being a beautiful draughtsman in itself is not enough." "Artists have always used other artists to help them do things. Doesn't he think Hirst is taking the mickey when he gets his mates in to do the paintings and then passes them off as his own? Absolutely not, Rosenthal says. Hirst was doing his dot paintings and Rosenthal thought they were marvellous. He reminisces about the great day back in the late 1980s when Hirst picked him up in his old banger and whizzed him off to see his Freeze shows. He's a big friend of Damien Hirst." And Damien Hirst is, of course, a big friend of Rosenthal's. "Exactly," he says: "I do know Alex from Blur quite well. "I think you mean Oasis," his PR Caroline says. We're going back a few years here, I say. Uhuh? I may know people from Blur, but I can't tell the difference when I listen to Blur and what's that other big band?" "I have never been interested in pop music. "I didn't like other children much because I wasn't interested in their interests. Yes, he says today, that seems fair enough. Rosenthal once said that as a child he was insecure and haughty. You can't believe it: German peasant emancipation in eastern Prussia in the 18th century." "Shall I tell you what I was going to do research into? Uhuh. He did a degree in history at Leicester and was about to become a postgraduate scholar when he wangled his way into his first job in a small gallery. His parents took him to the opera once a year, he watched the BBC Symphony Orchestra perform opposite his house in Maida Vale, he discovered Shakespeare at the Old Vic. As a boy, he was curious a culture vulture. His father ran a restaurant for emigres in London. Much of his family was wiped out in the Holocaust. His parents, Jewish refugees from Germany and Slovakia, fled Hitler. The chances of me dropping things are too great.

"It's delightful, isn't it? Uhuh?" I tell him I always want to touch the sculptures. Rosenthal is so obviously thrilled by the exhibition. At times, he is intimidating, at times sweet and childlike.

He leads me from piece to piece with a quick jab or tug of my shirt. "He's a kind of bird-man-God the God of wind." With his bulging eyes and squat body, and smart Fauvist shirt and tie, he looks like a dapper toad. I can never pronounce these names." But he can.

#Norman rosenthal supermind how to#

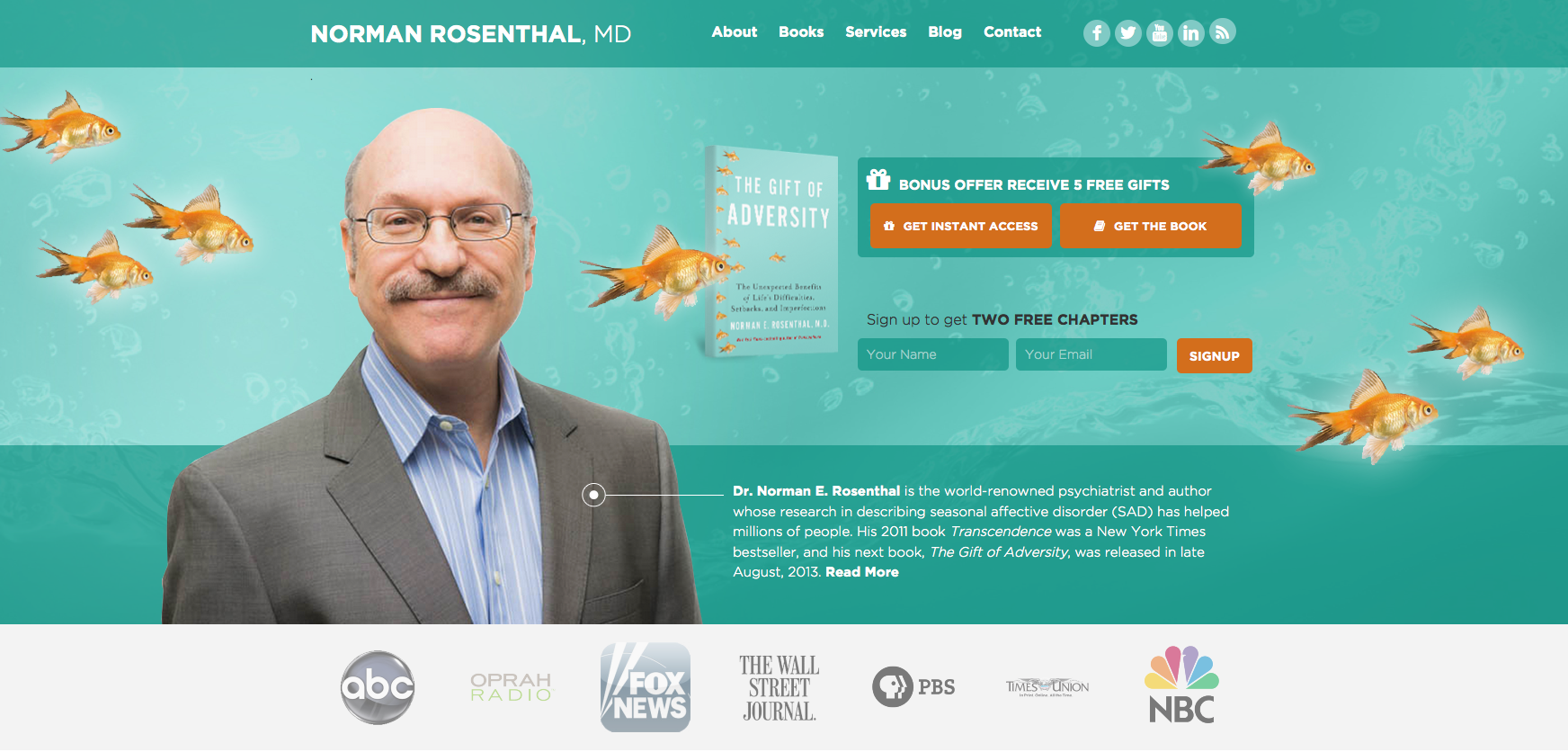

Rosenthal knows just how to make art accessible - it's great to see inner-city schoolkids dashing around the academy, alongside the toffs. As well as trumpeting the established classics (Mantegna, Botticelli), he is a great populariser of the ancient (the Aztecs), the obscure (the little-known painter Charlotte Salomon, who died in Auschwitz) and the new (Sensation, the Britart blockbuster). Today, it is one of the world's great exhibition spaces. When he arrived at the Royal Academy 25 years ago, it was a fusty and largely irrelevant institution. While other gallery directors find themselves bogged down in bureaucracy, in running an institution, Rosenthal can devote his time to conjuring up the dreamiest exhibitions. He occupies a unique and enviable role in British art. Rosenthal is the master of the big production. It has taken him seven years to put together, and he calls it a big production. Rosenthal, the exhibitions secretary at the Royal Academy, is to lead me through his marvellous Aztecs show. The noise is involuntary - part primeval grunt, part existential question. N orman Rosenthal looks me up and down, dismissively.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)